http://stevengoddard.wordpress.com/2013/07/12/western-arctic-sea-ice-coverage-third-highest-on-record/

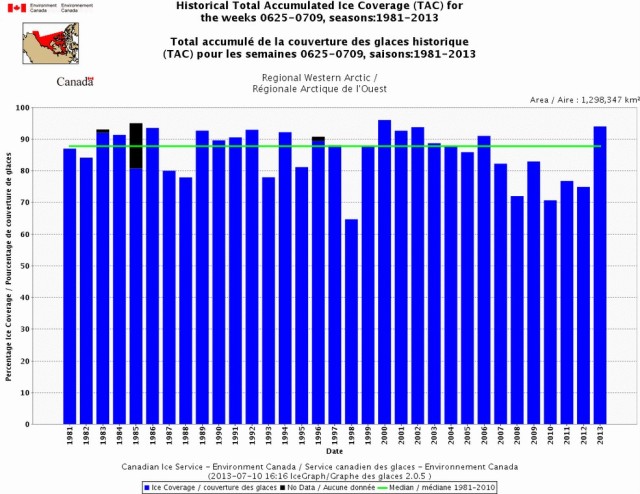

Western Arctic Sea Ice Coverage Third Highest On Record

I wonder why no one bothered to tell the rowers about this before they left Vancouver?

http://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/exploration/Crossing-the-Northwest-Passage.html?page=all

OUTSIDE ONLINE

WEDNESDAY, JULY 10, 2013

WEDNESDAY, JULY 10, 2013

ROWING THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE—BECAUSE THEY CAN

Four men are attempting to row a small fiberglass boat through a notorious Arctic route that has claimed the lives of countless explorers. Why? Because it's now possible, thanks to climate change.

By: SCOTT YORKO

A 100-year-old Inuit inukshuk serves as a landmark for seafarers in a fjord of Baffin Island, Nunavut, Canada.Photo: City Escapes Nature Photography

Kevin Vallely has seen human remains emerging from the hard, cold earth on King William Island, an Arctic archipelago just north of the Nunavut mainland. In August 2007, the now 48-year-old Canadian adventurer happened upon bones scored with blade marks and cracked open by desperate sailors scavenging for marrow in the depths of cannibalism.

Vallely was searching for evidence of Sir John Frankin’s tragically failed 1845 expedition to navigate a Northwest Passage trade route from England to the Orient, and although Franklin’s two ships have never been found, unidentified vertebrae and a scapula sit perched, as a memorial, on a stone cairn.

“The expedition history of doom and gloom up there is very profound,” says Vallely, who previously held the speed record for skiing to the South Pole.

But the Northwest Passage is increasingly easier to cross, thanks to a dramatic decrease in the volume of sea ice in recent years—more than a 50-percent reduction between 2005 and 2011, according to The Arctic Institute.

To draw attention to this startling fact, Vallely and his 3-man crew are attempting the first human-powered traverse of the Northwest Passage in a single season. Taking rotations in the two-man cockpit will be Paul Gleeson, an Irishman who rowed across the Atlantic in 2005; Frank Wolf, a Canadian filmmaker who biked, hiked, and paddled the proposed route of the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline; and Denis Barnett, a former Irish rally car driver who works in Vancouver’s shipping industry and locked down their deep-pocketed sponsor (Mainstream Renewable Power, a big alternative energy company) through his girlfriend.

The four men will spend the next 70-80 days rowing a 25-foot fiberglass boat, the Arctic Joule,1,800 miles east from Inuvik to Pond Inlet. Launching July 5, they're off to a late start, but still have plenty of time before the ice in the Admunsen Gulf fractures so that they can pass.

Their relatively puny 1,000-pound boat will tackle waters that previously required 5,000-ton icebreakers to cross, an indication of just how rapidly global warming is changing the Arctic.

At The Economist’s Arctic Summit in Oslo this past March, Vallely gave the keynote address to 150 attendees, from environmentalists to oil tycoons, aboard the Fram, the ship Norwegian explorer Roald Admunsen sailed to Antarctica before reaching the South Pole. No one at the conference denied the reality of global warming, and both sides of the climate change debate are intently interested in how it will affect the Arctic.

Environmentalists are concerned that decreasing temperatures will melt substantial permafrost, releasing methane, a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Energy companies, on the opposite end, are paying close attention to the growing accessibility in the Arctic of what the U.S. Geological Survey estimates to be "13 percent of the [world's] undiscovered oil, 30 percent of the undiscovered natural gas, and 20 percent of the undiscovered natural gas liquids." Even more attractive to prospective fossil fuel investors is the fact that this area is not subject to Canada's tariffs and regulations.

How much of an impact will a "raising awareness" expedition like this have on energy consumption and environmental protection? Climate change skeptics will likely dismiss it as a daredevil stunt enabled by a hefty sponsorship from an alternative energy company—but Vallely hopes that the combination of adventure and observation will provide as powerful a narrative as the 20th-century Arctic expeditions that imprinted on our psyche.

"To my mind, exploration is about seeking knowledge," says Vallely. "Although we're not exploring a new territory, we are certainly seeking knowledge in a changing environment. We're hoping to go up there and come to terms with what's changing from the perspective of the Inuit people. Rather than a pure adrenaline adventure like a wing-suited BASE jump, we're hoping there's more to this."

But he won't deny that there's a good bit of serious risk to go around. Rowing a boat for three months in Arctic temperatures might be more plausible today than it was a decade ago, but it’s not a whole lot safer. You still have to contend with monthlong storms, hungry polar bears, and rogue slabs of boat-crushing ice.

The biggest danger for Arctic sea navigation, particularly in the area west of King William Island, has often been strong northwest winds blowing in layers of multi-year ice, slowly pinning ships and immobilizing them for months on end. Without an engine, Vallely and his crew will have to be extremely careful to avoid getting blown into a slurry of ice, which could capsize their boat. But in the words of Roald Admunsen, “Adventure is just bad planning.”

The Grub960 packets oatmeal640 dehydrated meals

700 Powerbars

700 chocolate bars

500 Raman noodles

20 lbs coffee

6 containers coffee creamer

15 lbs beef jerky

6 bottles single malt (it ain’t all misery)

360 packets of vitamins

WHERE IS THE ARCTIC JOULE? Still waiting after three days for the winds to subside... AND THE ICE AHEAD TO MELT... You cannot row a boat into 25kts of wind caused from Global Warming... NOR THROUGH SEA ICE... THIS GLOBAL WARMING HYPERBOLA IS 'MONEY BUSINESS' TO FURTHER A CARBON POLLUTION TAX... IT IS NOT ABOUT SOLVING A PROBLEM BUT RATHER FROM BENEFITING FROM THE PERCEPTION OF CONTINUING THE MEDIA CIRCUS OF MIS-INFORMATION KEEPING THE PERCEIVED PROBLEM IN FRONT OF THE PUBLIC WHICH THEN APPEARS REAL AS IT MUST BE - YOU SEE IT EVERYWHERE. HOG WASH!

THANK GLOBAL WARMING FOR THE COLDEST ARCTIC SUMMER ON RECORD? WHY THEN DOES THE MEDIA SAY THE ICE IS GOING TO BE ALL MELTING IN THE NEAR FUTURE? RECORD COLD MELTS ICE? THE MEDIA CIRCUS DOES NOT REPORT GOOD SCIENCE - IT REPORTS SENSATIONAL INFORMATION AND EVENTS THAT SELL NEWSPAPERS, AD SPACE... IT IS ALL ABOUT REVENUES... M-O-N-E-Y TALKS AND BS WALKS!

THAT IS WHY THELASTFIRST EXPEDITION CREW IS OFF OF THEIR EAST VANCOUVER SIDE AFFLUENT PARK BENCH AND IN THE ARCTIC - MAINSTREAM RENEWABLE POWER (MRP IS BASED IN IRELAND) AND BECAME A SPONSOR AND PAID FOR THESE LADS TO GO ON A PAID VACATION TO THE ARCTIC TO ROW ROW ROW THEIR BOAT... LIFE IS SUCH A DREAM...

IF MRP REALLY WANTED TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE THEY WOULD ALSO BE OFFERING INCENTIVES ($) TO SELL RENEWABLE POWER SYSTEMS, I.E. SOLAR COMES TO MIND, WHICH LASTS FOR TENS OF YEARS RATHER THAN JUST PAYING THE EXPENSES FOR THESE 4 LADS TO GO ROW A BOAT IN THE ARCTIC WHICH WILL LAST ONLY A FEW MONTHS... I THINK, MRP IS COUNTING ON MORE "ADVENTURE" TO DRAW ATTENTION TO THEIR SPONSORSHIP... BUT WILL ANYONE BUY MRP PRODUCTS BECAUSE THEY SPONSORED A DARE DEVIL STUNT IN THE ARCTIC? DEFINITELY NOT! SO WHY THEN DID MRP SPONSOR SUCH A STUNT? ASK "FAST EDDIE" CEO TO EXPLAIN IT ON A BUSINESS LEVEL - NOT WITH CLIMATE CHANGE AND GLOBAL WARMING HYPERBOLE... WHAT SAY YOU EDDIE? I THINK HE IS PLANNING A CORPORATE VACATION HIMSELF TO MEET THE LADS IN THE ARCTIC... THEN MIGHT AWARD THEM ALL ELECTRIC CARS TO FURTHER SHOW HIS COMMITMENT TO SUPPORTING A CARBON TAX. REMEMBER - JUST FOLLOW THE M-O-N-E-Y... IT LIKELY WILL LEAD YOU TO THE ULTIMATE CORPORATE PERK... GREED! JUST ASK WHO WILL BENEFIT AT MRP THE MOST? LIKELY "FAST EDDIE"?

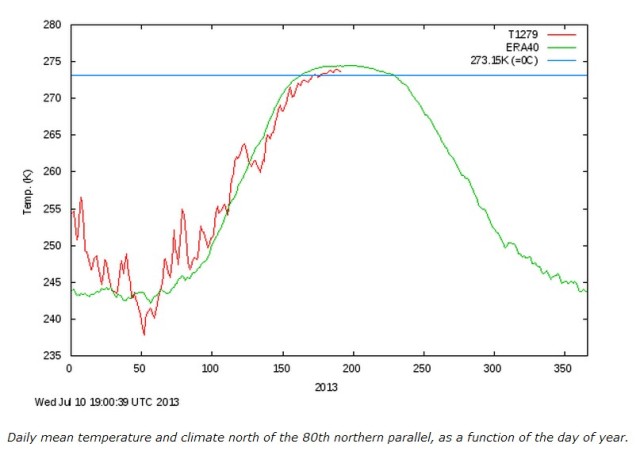

Half Way Through The North Pole Melt Season – Still The Coldest Summer On Record

The sun is getting lower in the sky now, and temperatures near the North Pole have been record cold this summer.

Climate Expert von Storch: Why Is Global Warming Stagnating?

Climate experts have long predicted that temperatures would rise in parallel with greenhouse gas emissions. But, for 15 years, they haven't. In a SPIEGEL interview, meteorologist Hans von Storch discusses how this "puzzle" might force scientists to alter what could be "fundamentally wrong" models.

SPIEGEL: Mr. Storch, Germany has recently seen major flooding. Is global warming the culprit?

Storch: I'm not aware of any studies showing that floods happen more often today than in the past. I also just attended a hydrologists' conference in Koblenz, and none of the scientists there described such a finding.SPIEGEL: But don't climate simulations for Germany's latitudes predict that, as temperatures rise, there will be less, not more, rain in the summers?

Storch: That only appears to be contradictory. We actually do expect there to be less total precipitation during the summer months. But there may be more extreme weather events, in which a great deal of rain falls from the sky within a short span of time. But since there has been only moderate global warming so far, climate change shouldn't be playing a major role in any case yet.

SPIEGEL: Would you say that people no longer reflexively attribute every severe weather event to global warming as much as they once did?

Storch: Yes, my impression is that there is less hysteria over the climate. There are certainly still people who almost ritualistically cry, "Stop thief! Climate change is at fault!" over any natural disaster. But people are now talking much more about the likely causes of flooding, such as land being paved over or the disappearance of natural flood zones -- and that's a good thing.

SPIEGEL: Will the greenhouse effect be an issue in the upcoming German parliamentary elections? Singer Marius Müller-Westernhagen is leading a celebrity initiative calling for the addition of climate protection as a national policy objective in the German constitution.

Storch: It's a strange idea. What state of the Earth's atmosphere do we want to protect, and in what way? And what might happen as a result? Are we going to declare war on China if the country emits too much CO2into the air and thereby violates our constitution?

SPIEGEL: Yet it was climate researchers, with their apocalyptic warnings, who gave people these ideas in the first place.

Storch: Unfortunately, some scientists behave like preachers, delivering sermons to people. What this approach ignores is the fact that there are many threats in our world that must be weighed against one another. If I'm driving my car and find myself speeding toward an obstacle, I can't simple yank the wheel to the side without first checking to see if I'll instead be driving straight into a crowd of people. Climate researchers cannot and should not take this process of weighing different factors out of the hands of politics and society.

SPIEGEL: Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, outside Berlin, is currently Chancellor Angela Merkel's climate adviser. Why does she need one?

Storch: I've never been chancellor myself. But I do think it would be unwise of Merkel to listen to just a single scientist. Climate research is made up of far too many different voices for that. Personally, though, I don't believe the chancellor has delved deeply into the subject. If she had, she would know that there are other perspectives besides those held by her environmental policy administrators.

SPIEGEL: Just since the turn of the millennium, humanity has emitted another 400 billion metric tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, yet temperatures haven't risen in nearly 15 years. What can explain this?

Storch: So far, no one has been able to provide a compelling answer to why climate change seems to be taking a break. We're facing a puzzle. Recent CO2 emissions have actually risen even more steeply than we feared. As a result, according to most climate models, we should have seen temperatures rise by around 0.25 degrees Celsius (0.45 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past 10 years. That hasn't happened. In fact, the increase over the last 15 years was just 0.06 degrees Celsius (0.11 degrees Fahrenheit) -- a value very close to zero. This is a serious scientific problem that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will have to confront when it presents its next Assessment Report late next year.

SPIEGEL: Do the computer models with which physicists simulate the future climate ever show the sort of long standstill in temperature change that we're observing right now?

Storch: Yes, but only extremely rarely. At my institute, we analyzed how often such a 15-year stagnation in global warming occurred in the simulations. The answer was: in under 2 percent of all the times we ran the simulation. In other words, over 98 percent of forecasts show CO2emissions as high as we have had in recent years leading to more of a temperature increase.

SPIEGEL: How long will it still be possible to reconcile such a pause in global warming with established climate forecasts?

Storch: If things continue as they have been, in five years, at the latest, we will need to acknowledge that something is fundamentally wrong with our climate models. A 20-year pause in global warming does not occur in a single modeled scenario. But even today, we are finding it very difficult to reconcile actual temperature trends with our expectations.

SPIEGEL: What could be wrong with the models?

Storch: There are two conceivable explanations -- and neither is very pleasant for us. The first possibility is that less global warming is occurring than expected because greenhouse gases, especially CO2, have less of an effect than we have assumed. This wouldn't mean that there is no man-made greenhouse effect, but simply that our effect on climate events is not as great as we have believed. The other possibility is that, in our simulations, we have underestimated how much the climate fluctuates owing to natural causes.

SPIEGEL: That sounds quite embarrassing for your profession, if you have to go back and adjust your models to fit with reality…

Storch: Why? That's how the process of scientific discovery works. There is no last word in research, and that includes climate research. It's never the truth that we offer, but only our best possible approximation of reality. But that often gets forgotten in the way the public perceives and describes our work.

SPIEGEL: But it has been climate researchers themselves who have feigned a degree of certainty even though it doesn't actually exist. For example, the IPCC announced with 95 percent certainty that humans contribute to climate change.

Storch: And there are good reasons for that statement. We could no longer explain the considerable rise in global temperatures observed between the early 1970s and the late 1990s with natural causes. My team at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, in Hamburg, was able to provide evidence in 1995 of humans' influence on climate events. Of course, that evidence presupposed that we had correctly assessed the amount of natural climate fluctuation. Now that we have a new development, we may need to make adjustments.

SPIEGEL: In which areas do you need to improve the models?

Storch: Among other things, there is evidence that the oceans have absorbed more heat than we initially calculated. Temperatures at depths greater than 700 meters (2,300 feet) appear to have increased more than ever before. The only unfortunate thing is that our simulations failed to predict this effect.

SPIEGEL: That doesn't exactly inspire confidence.

Storch: Certainly the greatest mistake of climate researchers has been giving the impression that they are declaring the definitive truth. The end result is foolishness along the lines of the climate protection brochures recently published by Germany's Federal Environmental Agency under the title "Sie erwärmt sich doch" ("The Earth is getting warmer"). Pamphlets like that aren't going to convince any skeptics. It's not a bad thing to make mistakes and have to correct them. The only thing that was bad was acting beforehand as if we were infallible. By doing so, we have gambled away the most important asset we have as scientists: the public's trust. We went through something similar with deforestation, too -- and then we didn't hear much about the topic for a long time.

SPIEGEL: Does this throw the entire theory of global warming into doubt?

Storch: I don't believe so. We still have compelling evidence of a man-made greenhouse effect. There is very little doubt about it. But if global warming continues to stagnate, doubts will obviously grow stronger.

SPIEGEL: Do scientists still predict that sea levels will rise?

Storch: In principle, yes. Unfortunately, though, our simulations aren't yet capable of showing whether and how fast ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica will melt -- and that is a very significant factor in how much sea levels will actually rise. For this reason, the IPCC's predictions have been conservative. And, considering the uncertainties, I think this is correct.

SPIEGEL: And how good are the long-term forecasts concerning temperature and precipitation?

Storch: Those are also still difficult. For example, according to the models, the Mediterranean region will grow drier all year round. At the moment, however, there is actually more rain there in the fall months than there used to be. We will need to observe further developments closely in the coming years. Temperature increases are also very much dependent on clouds, which can both amplify and mitigate the greenhouse effect. For as long as I've been working in this field, for over 30 years, there has unfortunately been very little progress made in the simulation of clouds.

SPIEGEL: Despite all these problem areas, do you still believe global warming will continue?

Storch: Yes, we are certainly going to see an increase of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) or more -- and by the end of this century, mind you. That's what my instinct tells me, since I don't know exactly how emission levels will develop. Other climate researchers might have a different instinct. Our models certainly include a great number of highly subjective assumptions. Natural science is also a social process, and one far more influenced by the spirit of the times than non-scientists can imagine. You can expect many more surprises.

SPIEGEL: What exactly are politicians supposed to do with such vague predictions?

Storch: Whether it ends up being one, two or three degrees, the exact figure is ultimately not the important thing. Quite apart from our climate simulations, there is a general societal consensus that we should be more conservative with fossil fuels. Also, the more serious effects of climate change won't affect us for at least 30 years. We have enough time to prepare ourselves.

SPIEGEL: In a SPIEGEL interview 10 years ago, you said, "We need to allay people's fear of climate change." You also said, "We'll manage this." At the time, you were harshly criticized for these comments. Do you still take such a laidback stance toward global warming?

Storch: Yes, I do. I was accused of believing it was unnecessary to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This is not the case. I simply meant that it is no longer possible in any case to completely prevent further warming, and thus it would be wise of us to prepare for the inevitable, for example by building higher ocean dikes. And I have the impression that I'm no longer quite as alone in having this opinion as I was then. The climate debate is no longer an all-or-nothing debate -- except perhaps in the case of colleagues such as a certain employee of Schellnhuber's, whose verbal attacks against anyone who expresses doubt continue to breathe new life into the climate change denial camp.

SPIEGEL: Are there findings related to global warming that worry you?Storch: The potential acidification of the oceans due to CO2 entering them from the atmosphere. This is a phenomenon that seems sinister to me, perhaps in part because I understand too little about it. But if marine animals are no longer able to form shells and skeletons well, it will affect nutrient cycles in the oceans. And that certainly makes me nervous.

SPIEGEL: Mr. Storch, thank you for this interview.

Interview conducted by Olaf Stampf and Gerald Traufetter

Storch: I'm not aware of any studies showing that floods happen more often today than in the past. I also just attended a hydrologists' conference in Koblenz, and none of the scientists there described such a finding.SPIEGEL: But don't climate simulations for Germany's latitudes predict that, as temperatures rise, there will be less, not more, rain in the summers?

Storch: That only appears to be contradictory. We actually do expect there to be less total precipitation during the summer months. But there may be more extreme weather events, in which a great deal of rain falls from the sky within a short span of time. But since there has been only moderate global warming so far, climate change shouldn't be playing a major role in any case yet.

SPIEGEL: Would you say that people no longer reflexively attribute every severe weather event to global warming as much as they once did?

Storch: Yes, my impression is that there is less hysteria over the climate. There are certainly still people who almost ritualistically cry, "Stop thief! Climate change is at fault!" over any natural disaster. But people are now talking much more about the likely causes of flooding, such as land being paved over or the disappearance of natural flood zones -- and that's a good thing.

SPIEGEL: Will the greenhouse effect be an issue in the upcoming German parliamentary elections? Singer Marius Müller-Westernhagen is leading a celebrity initiative calling for the addition of climate protection as a national policy objective in the German constitution.

Storch: It's a strange idea. What state of the Earth's atmosphere do we want to protect, and in what way? And what might happen as a result? Are we going to declare war on China if the country emits too much CO2into the air and thereby violates our constitution?

SPIEGEL: Yet it was climate researchers, with their apocalyptic warnings, who gave people these ideas in the first place.

Storch: Unfortunately, some scientists behave like preachers, delivering sermons to people. What this approach ignores is the fact that there are many threats in our world that must be weighed against one another. If I'm driving my car and find myself speeding toward an obstacle, I can't simple yank the wheel to the side without first checking to see if I'll instead be driving straight into a crowd of people. Climate researchers cannot and should not take this process of weighing different factors out of the hands of politics and society.

SPIEGEL: Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, outside Berlin, is currently Chancellor Angela Merkel's climate adviser. Why does she need one?

Storch: I've never been chancellor myself. But I do think it would be unwise of Merkel to listen to just a single scientist. Climate research is made up of far too many different voices for that. Personally, though, I don't believe the chancellor has delved deeply into the subject. If she had, she would know that there are other perspectives besides those held by her environmental policy administrators.

SPIEGEL: Just since the turn of the millennium, humanity has emitted another 400 billion metric tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, yet temperatures haven't risen in nearly 15 years. What can explain this?

Storch: So far, no one has been able to provide a compelling answer to why climate change seems to be taking a break. We're facing a puzzle. Recent CO2 emissions have actually risen even more steeply than we feared. As a result, according to most climate models, we should have seen temperatures rise by around 0.25 degrees Celsius (0.45 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past 10 years. That hasn't happened. In fact, the increase over the last 15 years was just 0.06 degrees Celsius (0.11 degrees Fahrenheit) -- a value very close to zero. This is a serious scientific problem that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will have to confront when it presents its next Assessment Report late next year.

SPIEGEL: Do the computer models with which physicists simulate the future climate ever show the sort of long standstill in temperature change that we're observing right now?

Storch: Yes, but only extremely rarely. At my institute, we analyzed how often such a 15-year stagnation in global warming occurred in the simulations. The answer was: in under 2 percent of all the times we ran the simulation. In other words, over 98 percent of forecasts show CO2emissions as high as we have had in recent years leading to more of a temperature increase.

SPIEGEL: How long will it still be possible to reconcile such a pause in global warming with established climate forecasts?

Storch: If things continue as they have been, in five years, at the latest, we will need to acknowledge that something is fundamentally wrong with our climate models. A 20-year pause in global warming does not occur in a single modeled scenario. But even today, we are finding it very difficult to reconcile actual temperature trends with our expectations.

SPIEGEL: What could be wrong with the models?

Storch: There are two conceivable explanations -- and neither is very pleasant for us. The first possibility is that less global warming is occurring than expected because greenhouse gases, especially CO2, have less of an effect than we have assumed. This wouldn't mean that there is no man-made greenhouse effect, but simply that our effect on climate events is not as great as we have believed. The other possibility is that, in our simulations, we have underestimated how much the climate fluctuates owing to natural causes.

SPIEGEL: That sounds quite embarrassing for your profession, if you have to go back and adjust your models to fit with reality…

Storch: Why? That's how the process of scientific discovery works. There is no last word in research, and that includes climate research. It's never the truth that we offer, but only our best possible approximation of reality. But that often gets forgotten in the way the public perceives and describes our work.

SPIEGEL: But it has been climate researchers themselves who have feigned a degree of certainty even though it doesn't actually exist. For example, the IPCC announced with 95 percent certainty that humans contribute to climate change.

Storch: And there are good reasons for that statement. We could no longer explain the considerable rise in global temperatures observed between the early 1970s and the late 1990s with natural causes. My team at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, in Hamburg, was able to provide evidence in 1995 of humans' influence on climate events. Of course, that evidence presupposed that we had correctly assessed the amount of natural climate fluctuation. Now that we have a new development, we may need to make adjustments.

SPIEGEL: In which areas do you need to improve the models?

Storch: Among other things, there is evidence that the oceans have absorbed more heat than we initially calculated. Temperatures at depths greater than 700 meters (2,300 feet) appear to have increased more than ever before. The only unfortunate thing is that our simulations failed to predict this effect.

SPIEGEL: That doesn't exactly inspire confidence.

Storch: Certainly the greatest mistake of climate researchers has been giving the impression that they are declaring the definitive truth. The end result is foolishness along the lines of the climate protection brochures recently published by Germany's Federal Environmental Agency under the title "Sie erwärmt sich doch" ("The Earth is getting warmer"). Pamphlets like that aren't going to convince any skeptics. It's not a bad thing to make mistakes and have to correct them. The only thing that was bad was acting beforehand as if we were infallible. By doing so, we have gambled away the most important asset we have as scientists: the public's trust. We went through something similar with deforestation, too -- and then we didn't hear much about the topic for a long time.

SPIEGEL: Does this throw the entire theory of global warming into doubt?

Storch: I don't believe so. We still have compelling evidence of a man-made greenhouse effect. There is very little doubt about it. But if global warming continues to stagnate, doubts will obviously grow stronger.

SPIEGEL: Do scientists still predict that sea levels will rise?

Storch: In principle, yes. Unfortunately, though, our simulations aren't yet capable of showing whether and how fast ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica will melt -- and that is a very significant factor in how much sea levels will actually rise. For this reason, the IPCC's predictions have been conservative. And, considering the uncertainties, I think this is correct.

SPIEGEL: And how good are the long-term forecasts concerning temperature and precipitation?

Storch: Those are also still difficult. For example, according to the models, the Mediterranean region will grow drier all year round. At the moment, however, there is actually more rain there in the fall months than there used to be. We will need to observe further developments closely in the coming years. Temperature increases are also very much dependent on clouds, which can both amplify and mitigate the greenhouse effect. For as long as I've been working in this field, for over 30 years, there has unfortunately been very little progress made in the simulation of clouds.

SPIEGEL: Despite all these problem areas, do you still believe global warming will continue?

Storch: Yes, we are certainly going to see an increase of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) or more -- and by the end of this century, mind you. That's what my instinct tells me, since I don't know exactly how emission levels will develop. Other climate researchers might have a different instinct. Our models certainly include a great number of highly subjective assumptions. Natural science is also a social process, and one far more influenced by the spirit of the times than non-scientists can imagine. You can expect many more surprises.

SPIEGEL: What exactly are politicians supposed to do with such vague predictions?

Storch: Whether it ends up being one, two or three degrees, the exact figure is ultimately not the important thing. Quite apart from our climate simulations, there is a general societal consensus that we should be more conservative with fossil fuels. Also, the more serious effects of climate change won't affect us for at least 30 years. We have enough time to prepare ourselves.

SPIEGEL: In a SPIEGEL interview 10 years ago, you said, "We need to allay people's fear of climate change." You also said, "We'll manage this." At the time, you were harshly criticized for these comments. Do you still take such a laidback stance toward global warming?

Storch: Yes, I do. I was accused of believing it was unnecessary to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This is not the case. I simply meant that it is no longer possible in any case to completely prevent further warming, and thus it would be wise of us to prepare for the inevitable, for example by building higher ocean dikes. And I have the impression that I'm no longer quite as alone in having this opinion as I was then. The climate debate is no longer an all-or-nothing debate -- except perhaps in the case of colleagues such as a certain employee of Schellnhuber's, whose verbal attacks against anyone who expresses doubt continue to breathe new life into the climate change denial camp.

SPIEGEL: Mr. Storch, thank you for this interview.

Interview conducted by Olaf Stampf and Gerald Traufetter

Translated from the German by Ella Ornstein

Hans von Storch, 63, is director of the Institute for Coastal Research at the Helmholtz Center Geesthacht for Materials and Coastal Research, near Hamburg. A mathematician and meteorologist, he ranks among the world's leading climate experts. At the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, he had an important role in analyzing the computer models used to simulate future climate changes.

Is our planet warming up by 1 degree Celsius, 2 degrees, or more? Is climate change entirely man made? And what can be done to counteract it? There are myriad possible answers to these questions, as well as scientific studies, measurements, debates and plans of action. Even most skeptics now concede that mankind -- with its factories, heating systems and cars -- contributes to the warming up of our atmosphere.

But the consequences of climate change are still hotly contested. It was therefore something of a political bombshell when unknown hackers stole more than 1,000 e-mails written by British climate researchers, and published some of them on the Internet. A scandal of gigantic proportions seemed about to break, and the media dubbed the affair "Climategate" in reference to the Watergate scandal that led to the resignation of US President Richard Nixon. Critics claimed the e-mails would show that climate change predictions were based on unsound calculations.

However, it seems all but impossible to provide conclusive proof in climate research. Scientific philosopher Silvio Funtovicz foresaw this dilemma as early as 1990. He described climate research as a "postnormal science." On account of its high complexity, he said it was subject to great uncertainty while, at the same time, harboring huge risks.

Although a British parliamentary inquiry soon confirmed that this was definitely not a conspiracy, the leaked correspondence provided in-depth insight into the mechanisms, fronts and battles within the climate-research community. SPIEGEL ONLINE has analyzed the more than 1,000 Climategate e-mails spanning a period of 15 years, e-mails that are freely available over the Internet and which, when printed out, fill five thick files. What emerges is that leading researchers have been subjected to sometimes brutal attacks by outsiders and become bogged down in a bitter and far-reaching trench war that has also sucked in the media, environmental groups and politicians.

SPIEGEL ONLINE reveals how the war between climate researchers and climate skeptics broke out, the tricks the two sides used to outmaneuver each other and how the conflict could be resolved.

From Staged Scandal to the Kyoto Triumph

The fronts in the climate debate have long been etched in the sand. On the one side there is a handful of highly influential climate researchers, on the other a powerful lobby of industrial associations determined to trivialize the dangers of global warming. This latter group is supported by the conservative wing of the American political spectrum, conspiracy theorists as well as critical scientists.

But that alone would not suffice to divide the roles so neatly into good and evil. Most climate researchers were somewhere between the two extremes. They often had difficulty drawing clear conclusions from their findings. After all, scientific facts are often ambiguous. Although it is generally accepted that there is good evidence to back forecasts of coming global warming, there is still considerable uncertainty about the consequences it will have.

Both sides -- the leading climate researchers on the one hand and their opponents in industry and smaller groups of naysayers on the other -- played hardball from the very beginning. It all started in 1986, when German physicists issued a dramatic public appeal, the first of its kind. They warned about what they saw as a "climatic disaster." However, their avowed goal was to promote nuclear power over carbon dioxide-belching coal-fired power stations.

The First Scandal

At the time, there was certainly clear scientific evidence of a dangerous increase in temperatures, prompting the United Nations to form the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 to look into the matter. However, the idea didn't take hold in the United States until the country was hit by an unusually severe drought in the summer of 1988. Politicians in Congress used the dry spell to listen to NASA scientist James Hansen, who had been publishing articles in trade journals for years warning about the threat of man-made climate change.

When Washington instructed Hansen to put more emphasis on the uncertainties in his theory, Senator and later Vice President Al Gore cried foul. Gore notified the media about the government's alleged attempted cover-up, forcing the government's hand on the matter.

The oil companies reacted with alarm and forged alliances with companies in other sectors who were worried about a possible rise in the price of fossil fuels. They even managed to rope in a few shrewd climate researchers like Patrick Michaels of the University of Virginia.

The aim of the industrial lobby was to focus as much as possible on the doubts about the scientific findings. According to a strategy paper by the Global Climate Science Team, a crude-oil lobby group, "Victory will be achieved when average citizens recognize uncertainties in climate science." In the meantime, scientists found themselves on the defensive, having to convince the public time and again that their warnings were indeed well-founded.

Industrial Propaganda for the 'Less Educated'

A dangerous dynamic had been set in motion: Any climate researcher who expressed doubts about findings risked playing into the hands of the industrial lobby. The leaked e-mails show how leading scientists reacted to the PR barrage by the so-called "skeptics lobby." Out of fear that their opponents could take advantage of ambiguous findings, many researchers tried to simply hide the weaknesses of their findings from the public.

The lobby spent millions on propaganda campaigns. In 1991, the Information Council on the Environment (ICE) issued a strategy paper aimed at what it called "less-educated people." This proposed a campaign that would "reposition global warming as a theory (not fact)." However, the skeptics also wanted to address better educated sectors of society. The Global Climate Coalition, for example, an alliance of energy companies, specifically tried to influence UN delegates. The advice of skeptical scientists was also given considerable credence in the US Congress.

Nonetheless, the lobbyists had less success on the international stage. In 1997, the international community agreed on the first-ever climate protection treaty: the Kyoto Protocol. "Scientists had issued a warning, the media amplified it and the politicians reacted," recalls Peter Weingart, a science sociologist at Bielefeld University in Germany, who researched the climate debate.

But just as numerous industrial firms began to acknowledge the need for climate protection and left the Global Climate Coalition, some scientists began getting too cozy with environmental organizations.

How Climate Researchers Plotted with Interest Groups

Even before the UN climate conference in Kyoto in 1997, environmentalist groups and leading climate researchers began joining forces to put pressure on industry and politicians. In August 1997, Greenpeace sent a letter to The Times newspaper in London, appealing on behalf of British researchers. All the climatologists had to do was sign on the dotted line. In October of that year, other climate researchers -- ostensibly acting on behalf of the World Wildlife Fund, or WWF -- e-mailed hundreds of colleagues calling on them to sign an appeal to the politicians in connection with the Kyoto conference.

The tactic was controversial. Whereas German scientists immediately put their names on the list, others had their doubts. In a leaked e-mail dated Nov. 25, 1997, renowned American paleoclimatologist Tom Wigley told a colleague he was worried that such appeals were almost as "dishonest " as the propaganda employed by the skeptics' lobby. Personal views, Wigley said, should not be confused with scientific facts.

Researchers 'Beef Up' Appeals by Environmental Groups

Wigley's calls fell on deaf ears, and many of his colleagues unthinkingly fell in line with the environmental lobby. Asked to comment by WWF, climate researchers in Australia and Britain, for example, made particularly pessimistic predictions. What's more, the experts said they had been fully aware that the WWF wanted to have the warnings "beefed up," as it had stated in an e-mail dated July 1999. One Australian climatologist wrote to colleagues on July 28, 1999, that he would be "very concerned" if environmental protection literature contained data that might suggest "large areas of the world will have negligible climate change."

Two years later, German climate researchers at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and from the Hamburg-based Max Planck Institute for Meteorology also drew up a position paper together with WWF. Germany's Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy scientific research institute was a pioneer in this respect. It was very open about working together with the environmental group BUND, the German chapter of Friends of the Earth, in developing climate protection strategy recommendations in the mid-1990s.

From then on, the battle was all about dominance of the media. The media are often accused of giving climate-change skeptics too much attention. Indeed theories that cast doubt over global warming with little scientific backing regularly appeared in the press. These included so-called "information brochures" sent to journalists by oil industry lobbyists.

This is partly because the US media, in particular, are extremely keen to ensure what they see as balanced reporting -- in other words, giving both sides in a debate a chance to air their views. This has meant that even more outlandish theories by climate-change skeptics have been given just as much airtime as the findings of established experts.

Media researchers believe the phenomenon of newsworthiness is another reason why anti-climate-change theories are reported so widely. The more unambiguous the warnings about an impending disaster, the more interesting critical viewpoints become. The media debate about the issue also focused on the potentially scandalous question of whether climatologists had speculated about nightmare scenarios simply in order to obtain access to research grants.

Renowned climate researcher Klaus Hasselmann of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology rebuffed these accusations in a much-quoted article in the German newspaper Die Zeit in 1997. Hasselmann pointed out that scientific findings suggest that there is an extremely high likelihood that man was indeed responsible for climate change. "If we wait until the very last doubts have been overcome, it will be too late to do anything about it," he wrote.

'Climatologists Tend Not to Mention their More Extreme Suspicions'

Hasselmann blamed the media for all the hype. In fact, sociologists have identified "one-up debates" in the media in which darker and darker pictures were painted of the possible consequences of global warming. "Many journalists don't want to hear about uncertainty in the research findings," Max Planck Institute researcher Martin Claussen complains. Sociologist Peter Weingart criticizes not just journalists but also scientists. "Climatologists tend not to mention their more extreme suspicions," he bemoans.

Whereas the debate flared up time and again in the US, "the skeptics in Germany were quickly marginalized again," recalls sociologist Hans Peter Peters of the Forschungszentrum Jülich research center, who analyzed climate-related reporting in Germany. Peters believes that the communication strategy of leading researchers has proven successful in the long run. "The announced climate problem has been taken seriously by the media," he says. He even sees signs of a "strong alignment of scientists and journalists in reporting about climate change."

Nonetheless, scientists have tried to apply pressure on the media if they disagreed with the way stories were reported. Editorial offices have been inundated with protest letters whenever news stories said that the dangers of runaway climate change appeared to be diminishing. E-mails show that climate researchers coordinated their protests, targeting specific journalists to vent their fury on. For instance, when an article entitled " What Happened to Global Warming?" appeared on the BBC website in October 2009, British scientists first discussed the matter among themselves by e-mail before demanding that an apparently balanced editor explain what was going on.

Social scientists are well aware that good press can do wonders for a person's career. David Philips, a sociologist at the University of San Diego, suggests that the battle for supremacy in the mass media is not only a means to mobilize public support, but also a great way to gain kudos within the scientific community.

Scientific Opinion Becomes Entrenched

The leaked e-mails show that some researchers use tactics that are every bit as ruthless as those employed by critics outside the scientific community. Under attack from global-warming skeptics, the climatologists took to the barricades. Indeed, the criticism only seemed to increase the scientists' resolve. And worried that any uncertainties in their findings might be pounced upon, the scientists desperately tried to conceal such uncertainties.

"Don't leave anything for the skeptics to cling on to," wrote renowned British climatologist Phil Jones of the University of East Anglia (UEA) in a leaked e-mail dated Oct. 4, 2000. Jones, who heads UEA's Climate Research Unit (CRU), is at the heart of the e-mail scandal. But there have always been plenty of studies that critics could quote because the research findings continue to be ambiguous.

At times scientists have been warned by their own colleagues that they may be playing into the enemy's hands. Kevin Trenberth from the National Center for Atmospheric Research in the US, for example, came under enormous pressure from oil-producing nations while he was drawing up the IPCC's second report in 1995. In January 2001, he wrote an e-mail to his colleague John Christy at the University of Alabama complaining that representatives from Saudi Arabia had quoted from one of Christy's studies during the negotiations over the third IPCC climate report. "We are under no gag rule to keep our thoughts to ourselves," Christy replied.

'Effective Long-Term Strategies'

Paleoclimatologist Michael Mann from Pennsylvania State University also tried to rein in his colleagues. In an e-mail dated Sept. 17, 1998, he urged them to form a "united front" in order to be able to develop "effective long-term strategies." Paleoclimatologists try to reconstruct the climate of the past. Their primary source of data is found in old tree trunks whose annual rings give clues about the weather in years gone by.

No one knows better than the researchers themselves that tree data can be very unreliable, and an exchange of e-mails shows that they discussed the problems at length. Even so, meaningful climate reconstructions can be made if the data are analyzed carefully. The only problem is that you get different climate change graphs depending on which data you use.

Mann and his colleagues were pioneers in this field. They were the first to draw up a graph of average temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 1,000 years. That is indisputably an impressive achievement. Because of its shape, his diagram was dubbed the "hockey stick graph." According to this, the climate changed little for about 850 years, then temperatures rose dramatically (the blade of the stick). However, a few years later, it turned out that the graph was not as accurate as first assumed.

'I'd Hate to Give It Fodder'

In 1999, CRU chief Phil Jones and fellow British researcher Keith Briffa drew up a second climate graph. Perhaps not surprisingly, this led to a row between the two groups about which graph should be published in the summary for politicians at the front of the IPCC report.

The hockey stick graph was appealing on account of its convincing shape. After all, the unique temperature rise of the last 150 years appeared to provide clear proof of man's influence on our climate. But Briffa cautioned about overestimating the significance of the hockey stick. In an e-mail to his colleagues in September 1999, Briffa said that Mann's graph "should not be taken as read," even though it presented "a nice tidy story."

In contrast to Mann et al's hockey stick, Briffa's graph contained a warm period in the High Middle Ages. "I believe that the recent warmth was probably matched about 1,000 years ago," he wrote. Fortunately for the researchers, the hefty dispute that followed was quickly defused when they realized they were better served by joining forces against the common

. Climate-change skeptics use Briffa's graph to cast doubt over the assertion that man's activities have affected our climate. They claim that if our atmosphere is as warm now as it was in the Middle Ages -- when there was no man-made pollution -- carbon dioxide emissions can't possibly be responsible for the rise in temperatures.

"I don't think that doubt is scientifically justified, and I'd hate to be the one to have to give it fodder," Mann wrote to his colleagues. The tactic proved a successful one. Mann's hockey stick graph ended up at the front of the UN climate report of 2001. In fact it became the report's defining element.

An Innocent Phrase Seized by Republicans

In order to get unambiguous graphs, the researchers had to tweak their data slightly. In probably the most infamous of the Climategate e-mails, Phil Jones wrote that he had used Mann's "trick" to "hide the decline" in temperatures. Following the leaking of the e-mails, the expression "hide the decline" was turned into a song about the alleged scandal and seized upon by Republican politicians in the US, who quoted it endlessly in an attempt to discredit the climate experts.

But what appeared at first glance to be fraud was actually merely a face-saving fudge: Tree-ring data indicates no global warming since the mid-20th century, and therefore contradicts the temperature measurements. The clearly erroneous tree data was thus corrected by the so-called "trick" with the temperature graphs.

The row grew more and more bitter as the years passed, as the leaked e-mails between researchers shows. Since the late 1990s, several climate-change skeptics have repeatedly asked Jones and Mann for their tree-ring data and calculation models, citing the legal right to access scientific data.

'I Think I'll Delete the File'

In 2003, mineralogist Stephen McIntyre and economist Ross McKitrick published a paper that highlighted systematic errors in the statistics underlying the hockey stick graph. However Michael Mann rejected the paper, which he saw as part of a "highly orchestrated, heavily funded corporate attack campaign," as he wrote in September 2009.

More and more, Mann and his colleagues refused to hand out their data to "the contrarians," as skeptical researchers were referred to in a number of e-mails. On Feb. 2, 2005, Jones went so far as to write, "I think I'll delete the file rather than send it to anyone."

Today, Mann defends himself by saying his university has looked into the e-mails and decided that he had not suppressed data at any time. However, an inquiry conducted by the British parliament came to a very different conclusion. "The leaked e-mails appear to show a culture of non-disclosure at CRU and instances where information may have been deleted to avoid disclosure," the House of Commons' Science and Technology Committee announced in its findings on March 31.

Sociologist Peter Weingart believes that the damage could be irreparable. "A loss of credibility is the biggest risk inherent in scientific communication," he said, adding that trust can only be regained through complete transparency.

From Deserved Reputations to Illegitimate Power

The two sides became increasingly hostile toward one another. They debated about whom they could trust, who was a part of their "team" -- and who among them might secretly be a skeptic. All those who were between the two extremes or even tried to maintain links with both sides soon found themselves under suspicion.

This distrust helped foster a system of favoritism, as the hacked e-mails show. According to these, Jones and Mann had a huge influence over what was published in the trade press. Those who controlled the journals also controlled what entered the public arena -- and therefore what was perceived as scientific reality.

All journal articles are checked anonymously by colleagues before publication as part of what is known as the "peer review" process. Behind closed doors, researchers complained for years that Mann, who is a sought-after reviewer, acted as a kind of "gatekeeper" in relation to magazine articles on paleoclimatology. It's well-known that renowned scientists can gain influence within journals. But it's a risky business. "The danger that deserved reputations become illegitimate power is the greatest risk that science faces," Weingart says.

From Peer Review to Connivance

In an e-mail to SPIEGEL ONLINE, Mann rejected the claims that he exercised undue influence. He said the editors of scientific journals -- not he -- chose the reviewers. However, as Weingart points out, in specialist areas like paleoclimatology, which have only a handful of experts, certain scientists can gain considerable power -- provided they have a good connection to the publishers of the relevant journals.

The "hockey team," as the group around Mann and Jones liked to call itself, undoubtedly had good connections to the journals. The colleagues coordinated and discussed their reviews among themselves. "Rejected two papers from people saying CRU has it wrong over Siberia," CRU head Jones wrote to Mann in March 2004. The articles he was referring to were about tree data from Siberia, a basis of the climate graphs. In fact, it later turned out that Jones' CRU group probably misinterpreted the Siberian data, and the findings of the study rejected by Jones in March 2004 were actually correct.

However, Jones and Mann had the backing of the majority of the scientific community in another case. A study published in Climate Research in 2003 looked into findings on the current warm period and the medieval one, concluding that the 20th century was "probably not the warmest nor a uniquely extreme climactic period of the last millennium." Although climate skeptics were thrilled, most experts thought the study was methodologically flawed. But if the pro-climate-change camp controlled the peer review process, then why was it ever published?

Plugging the Leak

In an e-mail dated March 11, 2003, Michael Mann said there was only one possibility: Skeptics had taken over the journal. He therefore demanded that the enemy be stopped in its tracks. The "hockey team" launched a powerful counterattack that shook Climate Research magazine to its foundations. Several of its editors resigned. Vociferous as they were, though, the skeptics did not have that much influence. If it turned out that alarmist climate studies were flawed -- and this was the case onseveral occasions -- the consequences of the climate catastrophe would not be as dire as had been predicted.

Yet there were also limits to the influence had by Mann and Jones, as became apparent in 2005, when relentless hockey stick critics Ross McKitrick and Stephen McIntyre were able to publish studies in the most important geophysical journal, Geophysical Research Letters (GRL). "Apparently, the contrarians now have an 'in' with GRL," Mann wrote to his colleagues in a leaked e-mail. "We can't afford to lose GRL."

Mann discovered that one of the editors of GRL had once worked at the same university as the feared climate skeptic Patrick Michaels. He therefore put two and two together: "I think we now know how various papers have gotten published in GRL," he wrote on January 20, 2005. At the same time, the scientists discussed how to get rid of GRL editor James Saiers, himself a climate researcher. Saiers quit his post a year later -- allegedly of his own accord. "The GRL leak may have been plugged up now," a relieved Mann wrote in an e-mail to the "hockey team."

Conclusive Proof Is Impossible

Climategate appears to confirm the criticism that scientific systems always benefit cartels. However, Sociologist Hans Peter Peters cautions against over-interpreting the affair. He says alliances are commonplace in every area of the scientific world. "Internal communication within all groups differs from the facade," Peters says.

Weingart also believes the inner workings of a group should not be judged by the criteria of the outside world. After all, controversy is the very basis of science, and "demarcation and personal conflict are inevitable." Even so, he says the extent to which camps have built up in climate research is certainly unusual.

Weingart says the political ramifications only fuelled the battle between the two sides in the global warming debate. He believes that the more an issue is politicized, the deeper the rifts between opposing stances.

Immense public scrutiny made life extremely difficult for the scientists. On May 2, 2001, paleoclimatologist Edward Cook of the Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory complained in an e-mail: "This global change stuff is so politicized by both sides of the issue that it is difficult to do the science in a dispassionate environment." The need to summarize complex findings for a UN report appears only to have exacerbated the problem. "I tried hard to balance the needs of the science and the IPCC, which were not always the same," Keith Briffa wrote in 2007. Max Planck researcher Martin Claussen says too much emphasis was put on consensus in an attempt to satisfy politicians' demands.

And even scientists are not always interested solely in the actual truth of the matter. Weingart notes that public debate is mostly "only superficially about enlightenment." Rather, it is more about "deciding on and resolving conflicts through general social agreement." That's why it helps to present unambiguous findings.

The Time for Clear Answers Is Over

The experts therefore face a dilemma: They have little chance of giving the right advice. If they don't sound the alarm, they are accused of not fulfilling their moral obligations. However, alarmist predictions are criticized if the predicted changes fail to materialize quickly.

Climatological findings will probably remain ambiguous even if further progress is made. Weingart says it's now up to scientists and society to learn to come to terms with this. In particular, he warns, politicians must understand that there is no such thing as clear results. "Politicians should stop listening to scientists who promise simple answers," Weingart says.

4 comments:

Very informative information. Thank you.

While I cannot, nor do scientists know for sure, the cause or cure for climate changes such as warming. What is for sure in my mind is that I cannot change things which in 100 years will make a noticeable difference to improve the quality of living on planet earth. I already use less fuels and powers, have invested in solar energy and use drip irrigation around my garden and house. Even if everyone started right now doing the same, until Governments come together and promote 'greener' powers without taxing for them will that one problem be reduced - not cured.

I see to many politicians being 'paid-off' by big business and not protecting and furthering the life, liberty and pursuit of happiness by their Citizens they have promised to represent. ALL politicians need to be limited to two terms in office, no retirements for life and be held accountable for the job they do - no get-out-of-jail cards or president saves.

Idealistic? Sure, but I love my country and have hope for my children. I will stand and fight before surrender.

Let the dare-devils jump... it stops idiots from reproducing....lol

Very rapidly this web site will be famous among all blogging

and site-building viewers, due to it's pleasant posts

Also visit my web page: Home based jobs (redecanais.tv)

I think that what you published was actually very logical.

But, think on this, what if you added a little content?

I ain't suggesting your content isn't good., however suppose you added a title that makes people want more?

I mean "ARCTIC JOULE cannot row in 25kts winds - BECAUSE SOMEONE PAID THEM TO ROW AGAINST GLOBAL WARMING" is

a little boring. You ought to peek at Yahoo's

home page and note how they write post titles to get people to click.

You might add a video or a pic or two to get readers interested about what you've written.

In my opinion, it could make your posts a little bit more interesting.

Check out my page ... need a job

Good point but like so many bloggers I have many things happening and so do not continually refine a post until a deadline... it comes was I find and know what is happening elsewhere... blending together... but I to agree - pictures make it more interesting as does a catchy title... but sometimes you grow tired of the idiots and move ahead to the next item of the todo list... keep reading... there are many items of interest down the road... :-)

Post a Comment

Enter your comment(s) here...