OSLO, NORWAY - Fram Museum director Geir Klover stands in front of the Gjoa in the new museum building, which is dedicated to the exploration of the Northwest Passage and is largely dominated by the 47-ton sloop named Gjøa that carried Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen through the first-ever navigation of the passage from 1903 to 1906. Photograph by: Andrea Hill / For Postmedia News , Postmedia News

OSLO, Norway – More than 4,000 kilometres from home, the mayor of a small Nunavut community can now find pieces of his town’s history in a new Norwegian museum building.

“I think it will better put us on the map,” said Joanni Sallerina, mayor of Gjøa Haven on King William Island in Nunavut. He was in Oslo last week to join the Norwegian king and prime minister for the grand opening of the Fram Museum’s new Gjøa building.

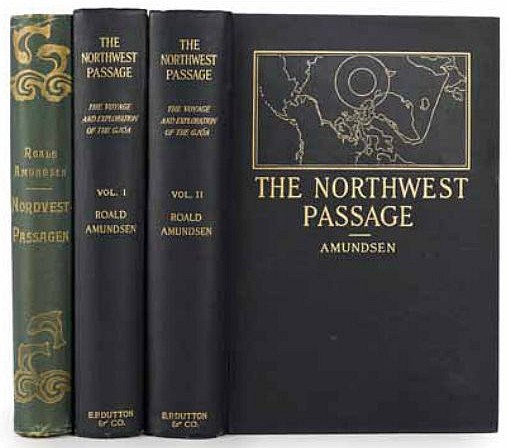

The building, dedicated to the exploration of the Northwest Passage, is largely dominated by the 47-ton sloop named Gjøa that carried Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen through the first-ever navigation of the passage from 1903 to 1906. But appearing alongside the ship are artifacts from Nunavut’s Netsilik Inuit — items Amundsen collected during the two winters he spent at the small hamlet that eventually became known as Gjøa Haven after his ship.

“Amundsen gathered everything,” said Geir Kløver, director of the Fram Museum. “Blubber lamps, drying racks, he even brought back two kayaks and several sledges. It documents the culture.”

But although Amundsen was the first to navigate the Northwest Passage and gathered the world’s largest collection of Netsilik artifacts, his story has largely been a “footnote” in Canadian history books, said Alberta-based author and historian Stephen Bown, who wrote a biography of Amundsen last winter. Bown said this is because Amundsen documented his journeys in Norwegian and that the explorer’s story will soon become better known now that the Fram Museum is translating the diaries of Amundsen and his crew into English.

“From a Canadian history point of view, the story should be so much more popular,” Bown said. “Amundsen had a huge influence on history and culture and he exposed the ideas and the practices of the Inuit people there to the world.”

When Amundsen first arrived at Gjøa Haven in the fall of 1903, the hamlet was deserted. The explorer put down anchor and set up observatories so his crew could take readings to determine the location of the magnetic North Pole, which moves over time. For a month, they made camp, manned the observatories and recorded weather conditions, including daily snowfall and temperature.

But then, a new learning opportunity presented itself.

In November of 1903, five Netsilik Inuit appeared on the horizon and Amundsen walked out to greet them with members of his crew. Though neither group could fully understand the other, both were excited to meet and an alliance was born that would last the next two years.

During that time, Amundsen traded with the Inuit and hired them as general labourers and teachers of Arctic survival. Word of the Europeans and their great ship spread throughout the region and soon large groups of Inuit began to gather.

“There really was no Gjøa Haven before he was there,” Bown said. “Most people at that time were very nomadic and so the very existence of Gjøa Haven is because of Amundsen’s ship.”

Over the next two years, Amundsen made detailed notes about Inuit customs and collected more than 1,000 Inuit artifacts, including traditional weapons and cooking utensils, that were given to the University of Oslo. He traded iron and steel products for warm reindeer-hide clothes and worked with Inuit teachers to master the skills of igloo building and dog sledding. Notably, the Netsilik taught him how to coat sledge blades with ice so they wouldn’t sink into the snow and how to tether sled dogs in a fan formation instead of a straight line so they have more room to manoeuvre around rough snow and other obstacles.

“Amundsen came there with a lot of respect for the people,” Bown said. “He came there admitting he was in a position of inferiority and he wanted to learn. He had a great respect for what was going on there in their way of life and how they were able to survive in such a challenging environment.”

The skills Amundsen learned from the Netsilik are largely credited for his later becoming the first person to reach the South Pole, which he accomplished in 1911. And the Netsilik are believed to have benefited from the interactions as well through their acquisition of materials and manufactured goods including cloth, wood, steel and firearms, which they otherwise wouldn’t have had access to. Sallerina said this aid is still remembered and celebrated in his community where people are very aware of Amundsen’s role in the founding of Gjøa Haven.

There, the explorer’s observatories remain preserved, guests can stay in an Amundsen hotel, a number of plaques throughout the city describe the explorer’s accomplishments and a new community hall is adorned with photos of Amundsen.

And with the opening of the Gjøa building this month, soon others outside of the small town will have an opportunity to learn about the explorer’s contributions to Canadian history, Sallerina said.

The building opened to the public just last week.

Read more:http://www.canada.com/news/Oslo+museum+highlights+strong+bond+between+Nunavut+town+explorer+Roald+Amundsen/8541790/story.html

No comments:

Post a Comment

Enter your comment(s) here...